Family & Home

The “Model Minority” Family

The “model minority” is affluent, highly educated, and unproblematic: the success story of all minorities in the United States. In the conception of the “model minority,” the family acts as a catalyst supporting that lifestyle. It is stable, structured, heteronormative, financially secure, and obedient, passing down these ideologies to each successive generation.

As part of a lineage of immigrants in the United States, Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) families struggle with compromising their own cultural heritage in order to become the “Normal American Family.” The family and home are quintessential players in shaping the lives of Asian Americans, especially their ties to culture, language, social customs and practices. Ultimately, home and family life inadvertently affect the educational and professional attainment of family members.

This page examines the importance of home life and family relationships of the AAPI community, specifically the stability of the nuclear family, “tiger mom” parenting strategies that allegedly raise successful, high-achieving “model minority” children, filial piety and familial obligations, the complexities of gender roles within the family, and the repercussions of the “model minority” label and its mentality of fierce competitiveness to succeed.

Home Away from Home

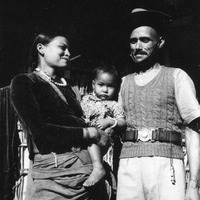

Immigration is strongly related to the stability and structure of the AAPI home. Prior to the conceptualization of the “model minority” in the mid-1960s, exclusionary acts and strict immigration laws prevented the formation of Asian nuclear families in the United States, as primarily men were sought to meet labor demands in agriculture and gold rushes. With U.S. immigration reform in the latter half of the twentieth century, Asians became the fastest growing minority group in the United States. Asian demographic numbers spiked from 800,000 in the 1960s to over 5 million in the 1980s (Divoky 220). This allowed AAPI communities to form more nuclear families and start a new generation of AAPIs.

…a new wave of skilled immigrants and students who entered the country after the landmark 1965 Immigration Act re-opened large-scale Asian immigration. Their education and class status position these immigrants as model minorities in an emerging US knowledge economy.— Susan Koshy, “Neoliberal Family Matters,” American Literary History, vol. 25, no. 2, 2013 (p. 350)

Some immigrants wished to provide better educational and economic opportunities for their children, pushing for social mobility in their own careers while encouraging their children to do the same in school so that they could do the same in the future. Other immigrant families relocated to the U.S. seeking peace and shelter in the United States in the aftermath of the consecutive wars in East and Southeast Asia (Korean War, Vietnam War, Southeast Asian War) that ravaged their home countries, namely Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. As elite professionals, students, or refugees, immigrants from Asia wanted to pursue a better life in the United States.

Immigrating to the U.S. often meant leaving behind family, friends, everything familiar — leaving one’s comfort zone. With language barriers, societal pressures, and racial prejudice and discrimination, the family home was a safe haven from discriminatory outside forces. After all, the home could retain a semblance of the native country through language, cultural norms, and family structure. Immigration to the United States was not only a lifetime investment for the entire family, but an initiation of the “Asian American” identity, as these immigrant families could bring their culture and language with them, but still had to adapt to another country. Asian immigrant families had to reconcile their cultural values and identities with the American mainstream and forge a new cultural identity — as AAPI.

First Gen Asian Immigrants Invest in the “Model Minority” Family

The “model minority” family revolves around committing to long-term investments. Immigrating to the United States and raising children are the two quintessential investments that often direct the lives of these AAPI families. However, this brings up the complicated and multilayered relationship of intergenerationality within the AAPI family. Despite being heralded as the “model minority family” that has become “an exemplary enterprise unit” (Koshy 346), relationships in the family can suffer under such high stake pressures to assimilate, retain cultural values, and succeed academically and professionally.

Seen through the lens of American capitalism, Asian immigration to the U.S. was fueled by economic incentives, especially when the 1965 Immigration Act opened U.S. borders mainly to skilled immigrant workers in search of human capital. This “economic migration” translated well with the popularization of the “model minority” title in the mid-1960s and the alleged widespread success of the Asian minority in the United States, as “the Asian American family [also came] to be identified as an intimate form ideally equipped to reproduce human capital” (Koshy 346). For AAPI, this successful reputation creeps into the mentality of AAPI homes alongside the preexisting desire to pursue better lives in the U.S. and secure the same for subsequent generations.

The neoliberal understanding of human abilities as sources of potential income redefines child-rearing by treating a broader range of activities of care and cultivation, and not only educational and professional training, as potential ‘investments’ in the human capital of children.— Susan Koshy, “Neoliberal Family Matters,” American Literary History, vol. 25, no. 2, 2013 (p. 345)

AAPI Intergenerationality: First VS. Second Generation

An important factor at play within the AAPI home is intergenerationality, as different generations of AAPI families may not share the same priorities or values in cultural heritage and identity, education, and financial security.

…the lives of the first generation as they seek to preserve cultural identity while pursuing economic mobility, and the next generation, who negotiate relentless parental expectations to reproduce professional success and maintain cultural continuity even as they deal with their outsiderness to American culture.— Susan Koshy, “Neoliberal Family Matters,” American Literary History, vol. 25, no. 2, 2013 (p. 352)

Cultural heritage and identity from the native country is often preserved by the first generation Asian immigrants, even as they work to climb the U.S. socioeconomic ladder. The second generation, however, is subjected to many additional pressures: to succeed academically and professionally, to fit in with their American peers at school, and also to maintain their cultural heritage in a country that does not practice those customs or share the same language.

First and second generation people frequently identify differently. First generation Asian immigrants inevitably feel closer to their home country, whereas their children, who grow up in American schools with American peers, forge new bicultural identities as second generation “Asian American Pacific Islanders” that are inherently different from their immigrant parents.

Apart from redefining their own cultural identity as Asian Americans, intergenerational rifts caused by economic migration and cultural marginalization reveals unspoken conflicts on future endeavors of AAPI family members as well.

The “Model Minority” Mother is a Tiger Mom

The idea of “tiger moms” comes from the desire to succeed, as “AAPIs believed that academic and educational achievement were means to rise above discrimination and to secure social mobility” (Pang, et al. 379). By pushing their children to perform better in school, chances of financial security in the future through higher education and a higher professional career path become more plausible. In many cases, first generation Asian immigrant parents ingrain the idea that doing well in school is a requirement to do well in the United States (Lee 418). Through success and high-achievement in education, Tiger Moms hope to better the chances for financial stability for their children.

Historically, as a response to social oppression and racism, AAPIs developed a mind-set of relative functionalism; to become successful, they and their children saw education as the best avenue for pursuing the American Dream.— Valerie Ooka Pang, et al. “Asian American and Pacific Islander Students: Equity and the Achievement Gap.” Educational Researcher, vol. 40, no. 8, 2011 (p. 379)

Parents become academic coaches towards their children not to fulfill the expectations of the successful “model minority” but rather to secure a stable financial future in an institutionally biased society. The Tiger Mom enforces rigorous study habits as a precautionary measure, to ensure that the social injustices that their children might encounter in the future will not hinder their socioeconomic status, which might be considered the measure of happiness and stability for these immigrant AAPI parents.

The backbone behind the Asian immigrant family is the value of relentless “emotional and mental discipline as the formula for economic success and family unity in the turbulent tides of globalization” (Koshy 348). And in the United States, Asian immigrants inevitably encounter the American social hierarchies: by gender, socioeconomic status, and race. Institutionalized racism favoring white Americans instills a sense of “relative functionalism” in AAPIs, in which putting in more hours and working twice as hard just to make nearly as much as the average (white) American (Pang, et al. 379). An example in one study featured Japanese Americans with 1-2 years more schooling than their white American counterparts, however, their salaries were lower and their positions were less prestigious (379). Similarly, national corporations commonly incorporate a glass ceiling, so that AAPIs were “less likely to advance into leadership positions” (379).

The history of AAPIs demonstrates that racism and social oppression have been barriers to their full inclusion in this democracy. In response to racial and ethnic bias, elders, parents, and others shared with their families historical examples of discrimination and then conveyed to youth that they must work harder and accomplish more than their mainstream peers in order to succeed. Therefore, relative functionalism is a pragmatic response to a long history of exclusion and exploitation.— Valerie Ooka Pang, et al. “Asian American and Pacific Islander Students: Equity and the Achievement Gap.” Educational Researcher, vol. 40, no. 8, 2011 (p. 379)

Issues surrounding intergenerationality are multilayered within the “model minority” home, as it is shaped by a complex network of obligation and indebtedness to family. It is argued by scholars and researchers that intergenerationality for the “model minority” family becomes inescapably “debt-bound” as the family structure assumes compensatory attitudes towards the preceding generation.

[There is] an urgency to reproduce cultural identity and economic success to compensate for the parental losses of dislocation, to vindicate departure from the homeland to relatives left behind, to accrue cultural capital within competitive diaspora social networks, and to neutralize the liabilities of minority status.— Susan Koshy, “Neoliberal Family Matters,” American Literary History, vol. 25, no. 2, 2013 (p. 357)

The “Normal American Family” VS. the “Model Minority” Family

Television families and non-Asian (white) American families are often held up as the “model” American family AAPIs grow up comparing and contrasting family values, structures, and practices of the “Normal American Family” with their own, regardless of how inaccurate the depiction of the average American household may be. This framework not only creates fissures between the generations, who are both accustomed to different cultural family ties and responsibilities within the family structure, but shapes their individual priorities and worldviews as well.

Children in the United States grow up vicariously experiencing life in these television families, including children of immigrants who rely on television to learn about American culture [where the] TV [becomes] an immense ‘assimilative’ force for today’s children of immigrants [which] remains to be studied how their worldviews are shaped by such ‘cultural propaganda’.— Pyke, Karen. “‘The Normal American Family’ as an Interpretive Structure of Family Life among Grown Children of Korean and Vietnamese Immigrants.” Journal of Marriage and Family, vol. 62, no. 1, 2000 (p. 241)

AAPI parental figures, facing different priorities and challenges than their white counterparts, are frequently perceived as aggressive and cold in contrast with American families, who are typically represented by parents who are kind and openly loving towards their children.

In Pyke’s extensive research on Korean and Vietnamese immigrants who grew up in the United States, Pyke found that second generation children felt as if their immigrant parents were “unloving” because of their distant, aloof disposition and lack of open displays of affection. Strictness and harsh criticisms from these parents were interpreted by AAPI children negatively, when in fact, these strict child-rearing practices were common in Asia, and even “in Korea, children were found to associate parental strictness with warmth and concern and its absence as a sign of neglect” (Pyke 242).

As a result of more Americanized worldviews, parent-child conflicts and cultural gaps exist in many AAPI families. However, the “model minority” masks many of these issues, as the label silences any closer examination of the mechanisms at play of these issues because it assumes the stability of the AAPI home (243).

The images seen on television serve as powerful symbols of the ’normal’ family or the ‘good’ parent—and they often eclipse our appreciation of diverse family types.— Pyke, Karen. “‘The Normal American Family’ as an Interpretive Structure of Family Life among Grown Children of Korean and Vietnamese Immigrants.” Journal of Marriage and Family, vol. 62, no. 1, 2000 (p. 241)

AAPI students also use the “Normal American Families” featured on television as a way to measure or gauge their own assimilation into American culture. However, the prioritization of cultural integrity and typical Asian family structure of the first generation is at odds with more Americanized second generation AAPIs, who value “prevailing [American] family images [that] emphasize sensitivity, open honest communication, flexibility, and forgiveness” rather than traits that are more commonly stressed in Asian cultures: duty, responsibility, obedience, and “commitment to the family collective that supersedes self-interests” (Pyke 241). Yet, U.S. popular culture often functions as an instrument for assimilation in immigrant families.

Traditional family structures from different cultures are inevitably different. American family ideals emphasize democratic relations, individual autonomy, psychological well-being, and emotional expressiveness (Pyke 241), whereas many Asian cultures feature more authoritarian relations that focus on duty and discipline in traditional family structures. AAPI families therefore face difficulties reconciling American family ideals with their own and giving rise to the AAPI ethnic identity in contemporary United States, “from the shared experiences of growing up American in an Asian home” (Pyke 244).

The Patriarchy of the “Model Minority” Family

When coming to the United States, immigrants inevitably bring with them the values and social structures of their own cultures. The Asian immigrant household is typically patriarchal, creating a gendered division of power, labeling the man as the “head” of the household, as well as investing the family wealth and resources in the firstborn son (Lee, A New History of Asian America, p. 95-117). Wives often become stay-at-home “tiger moms” who hover over the children to ensure they are obediently meeting expectations. AAPI families inherit these norms in accordance with the traditions of their native countries.

Adapting to an American lifestyle and society, “the burden of accommodation falls heavily on women and the second generation” (Koshy 357). Immigration to the United States in the mid-nineteenth century was first geared towards male manual laborers, preventing the widespread formation of nuclear Asian families in the U.S. until after WWII and the 1965 Immigration Act, when more Asian women were allowed to immigrate. As a result, the Asian immigrant woman fell under a “secondary” role, as men more often came to the U.S. for educational and economic opportunities, while women immigrated as homemakers (352).

Due to the patriarchal nature of the family, the prioritization of the firstborn son then prioritizing the next sons before any daughters, was a cause for criticism towards the parents by their AAPI children. Second generation AAPI daughters complain that “parents grant more freedom and respect to sons” while sons complain about strict parents, but “acknowledged receiving more respect and freedom than sisters” (Pyke 244). Many first generation Asian immigrant parents do not believe this child-rearing sexism to be a problem, coming from many Asian cultures that follow the same patriarchal formula in raising families, generating more intergenerational conflicts. For second generation AAPI children, growing up more Americanized and familiar with themes of gender equity in the United States, there is a pressing consciousness of the issue of gender, especially within the patriarchal “model minority” family.

The sons and daughters of “model minority” families are faced with different struggles and expectations in life. In the past, traditional Asian family ideals valuing the firstborn son before other sons and before daughters were more apparent. In more recent times, progressive ideals and the superimposing Americanization of popular culture pushes for more gender equality within the “model minority” family. Depending on the generation, the Americanization of the family, the tradeoff between traditional and more progressive family values and ideals varies.

The “Model Minority” Family is an American Family

Asian immigrants come to the United States for educational and economic opportunities, or seeking refuge. Whatever the case may be, Asian immigrants arrive in the U.S. aware of the socioeconomic pyramid already in place, however, the preexisting racial hierarchy of American society adds another layer of complexity to AAPI assimilation. Their “economic migration penetrates the emotional infrastructure of the family, distorting filiality and disrupting belonging” (Koshy 350), which is the most apparent between the first and second generation AAPIs, who are tasked with consolidating Americanized Asian ideals for the AAPI family.

The social context of AAPIs must also be considered. Not only are AAPI students and their parents members of minority subcultures; they also live within a mainstream society where they face societal oppression based on their race.— Valerie Ooka Pang, et al. “Asian American and Pacific Islander Students: Equity and the Achievement Gap.” Educational Researcher, vol. 40, no. 8, 2011 (p. 386-7)

Diverse cultural backgrounds and socioeconomic statuses puts Asian immigrants in the United States in a unique situation in which they must find a way to reconcile their cultural identity with the superimposed American one. Family structure and traditional family values of immigrant Asian families are in direct opposition to the popular “Normal American Family” ideals, causing rifts between the first and second generation AAPIs who perceive displays of affection and familial love differently.

The “model minority” family and home is an image projected over a diverse demographic group coming to the U.S. under a variety of different circumstances. It falsely imagines a picture perfect AAPI family that is perhaps equally as propagandistic as the “Normal American Family,” because the image of academic and economic success of the “model minority” family encourages people to believe that success and nonexistent domestic issues to be true for AAPI families. In turn, this affects the AAPI family adversely, as the “model minority” label turns the home into “an arena of unaccounted gendered labor and burdened filial relations, insisting on a reckoning of the costs of displacement” (Koshy 352).

Sources / References

Anna S. Lau, et al. “Parent-to-Child Aggression among Asian American Parents: Culture, Context, and Vulnerability.” Journal of Marriage and Family, vol. 68, no. 5, 2006, pp. 1261–1275. JSTOR, <www.jstor.org/stable/4122858>.

Divoky, Diane. “The Model Minority Goes to School.” The Phi Delta Kappan, vol. 70, no. 3, 1988, pp. 219–222. JSTOR, <www.jstor.org/stable/20403855>.

Huang, Guiyou. “Orientalism and Asian America.” The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Asian American Literature. Ed. Guiyou Huang. Vol. 3. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2009. p. 794-798.

Iceland, John. Popul Res Policy Rev (2019). “Racial and Ethnic Inequality in Poverty and Affluence, 1959–2015.” pp. 1-40. Springer Netherlands. Springer Nature B.V. 2019. <https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-019-09512-7>.

Julian, Teresa W., et al. “Cultural Variations in Parenting: Perceptions of Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic, and Asian-American Parents.” Family Relations, vol. 43, no. 1, 1994, pp. 30–37. JSTOR, <www.jstor.org/stable/585139>.

Koshy, Susan. “Neoliberal Family Matters.” American Literary History, vol. 25, no. 2, 2013, pp. 344–380., <www.jstor.org/stable/43817573>.

Lee, Shelley Sang-hee. “Americanization, Modernity, and the Second Generation through the 1930s.” A New History of Asian America, p. 95-117, Routledge, Taylor & Francis. 2014.

Nee, Victor, and Herbert Y. Wong. “Asian American Socioeconomic Achievement: The Strength of the Family Bond.” Sociological Perspectives, vol. 28, no. 3, 1985, pp. 281–306. JSTOR, <www.jstor.org/stable/1389149>.

Pang, Valerie Ooka, et al. “Asian American and Pacific Islander Students: Equity and the Achievement Gap.” Educational Researcher, vol. 40, no. 8, 2011, pp. 378–389. JSTOR, <www.jstor.org/stable/41302978>.

Pyke, Karen. “‘The Normal American Family’ as an Interpretive Structure of Family Life among Grown Children of Korean and Vietnamese Immigrants.” Journal of Marriage and Family, vol. 62, no. 1, 2000, pp. 240–255. JSTOR, <www.jstor.org/stable/1566701>.

Roshanravan, Shireen M. “Passing-as-If: Model-Minority Subjectivity and Women of Color Identification.” Meridians, vol. 10, no. 1, 2009, pp. 1–31. JSTOR, <www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/mer.2009.10.1.1>.

Weil, Jennifer M., and Hwayun H. Lee. “Cultural Considerations in Understanding Family Violence among Asian American Pacific Islander Families.” Journal of Community Health Nursing, vol. 21, no. 4, 2004, pp. 217–227. JSTOR, <www.jstor.org/stable/3427828>.