Activism

Toy received his Bachelors degree at Denison University in 1951 and received a master’s degree in Clinical Social Work from the University of Michigan. After graduating, Toy was an organist and Director of Music for St. Joseph’s Episcopal Church in Detroit, Michigan, where he became involved in local gay rights campaigns. It was also a center of the Vietnam War draft-resistance movement. He became a founding member of both the Detroit Gay Liberation Movement (DGLM) in 1970 and, subsequently, the Ann Arbor Gay Liberation Front (AAGLF).

Toy’s active involvement in gay liberation movement coincided with his engagement in the anti-Vietnam War work. He was the first person in Michigan to publicly come out as gay, and he did this in his speech at an anti-Vietnam War rally in Detroit in 1970, representing DGLM. As he began his speech, he “was inspired to share my name, my age, and the reality that I was gay. No other person in Michigan had come out publicly prior to that day.”

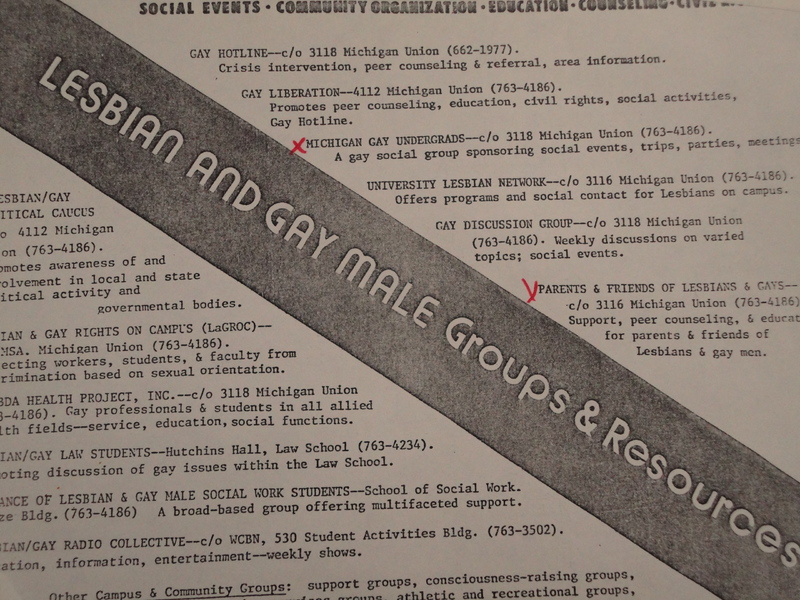

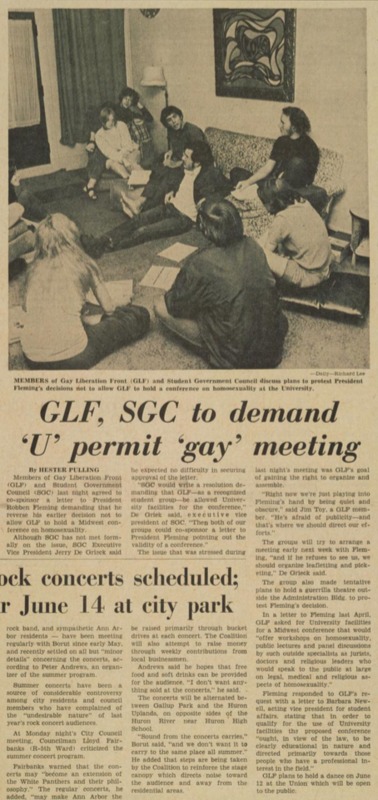

Following year, in 1971, he and the AAGLF successfully petitioned the University of Michigan for an office with paid staff to serve the needs of lesbian and gay-male students (Jim Toy Papers, Box 18). Initially known as the Human Sexuality Office, the University renamed it the LGMPO (Lesbian-Gay Male Programs Office), making it the first staffed university office in the United States to address sexual-orientation concerns. The office offered a space where members of the LGBTQ Community could receive support, counseling and safe haven. The office was later renamed the Spectrum Center, a name it still carries today.

The creation of HSO and later the Spectrum Center was revolutionary and took place during a turning point in the LGBTQ movement in the United States. Toy’s main goal for the office was to develop a safe space for the LGBTQ community within an environment that systematically discriminated against them as well as maintain a presence at the University of Michigan. Along with other activists, Toy battled several disagreements with city council and university administration about the LGBTQ presence on campus and the community (Spectrum Center Website). But, eventually, their efforts were successful. He also lobbied the University of Michigan to include sexual orientation in the nondiscrimination clause of its bylaws, eventually becoming successful in 1993.

Beyond the University, Toy’s early activism includes helping to draft an anti-discrimination ordinance for the City of Ann Arbor in 1972. It was called “Lesbian-Gay Pride Week Proclamation.” This ordinance made the Ann Arbor City Council one of the first governing bodies to officially recognize Gay Pride. Toy was involved in multiple organizations in Washtenaw County, such as the Ann Arbor Gay Hotline he co-founded in 1972, what is now known as the HIV/AIDS Resource Center in Washtenaw County (HARC), and the Washtenaw Rainbow Action Project (WRAP). He was a member of the Task Force on the Family and Sexuality of the Civil Rights Committee of the Michigan State House of Representatives. He served on the local chapter of the ACLU and many other organizations. He has been a University lecturer, and a community counselor and therapist. These efforts extended to advocacy for the trans community in Michigan, and collaboration with organizers to develop the Transgender Advocacy Project (TAP). Throughout, he also continued to work within the Episcopal community and other institutions to create more welcoming environments for the LGBTQ people and those identifying as a racial minority. Toy is a prominent voice in the queer Asian American community and inspires many queer identifying A/PIA people today.

Toy’s contribution to establishing a LGBTQ center and community at the University of Michigan is immeasurable. He began in Detroit and created a strong network of allies to push the movement forward with results that were concrete, politically viable and of long lasting influence. As artist, teacher, administrator, motivator, or counselor, Jim Toy remains one of the greatest talent that has shaped what the University of Michigan and the State of Michigan have become. We next examine more closely Toy’s accomplishment at the University and explore his intersectional understanding of social justice.

Intersection of Asian American and TBLGQI

The influence of the Civil Rights movement was felt on the Michigan campus, as Toy and others battled several administrative disagreements about the LGBTQ presence on campus as well as surveying the atmosphere on campus in relations to the community (Spectrum Center). In urging the administration to support the creation of a center for gay male and lesbian students, they reminded the University of the model it used in sponsoring organizations for black students and women students. In 1971, the University first sponsored the Human Sexuality Office with Jim Toy and Cynthia Gair as hired co-coordinators and “Lesbian Advocate” and “Gay Advocate” respectively. Toy’s first annual report states his ambition:

“to help gay people solve the problems they experience in a pre-dominately heterosexual society” and to help educate the University community and the community-at-large about the nature of sexuality and, specifically, homosexuality; about the oppression that people endure; and about the rights that gay people should enjoy.”

Toy outlined his goals for the future of the LGBTQ community on a campus that still held homophobic sentiments subtly reinforced by the administration: for the office to offer a safe space for the LGBTQ community within an environment that systematically discriminated against them and to develop an LGBTQ presence at the University of Michigan.

In various ways, Toy was instrumental in continuing research and outreach programs within the office with the goal to properly serve the students at the University of Michigan. He counseled LGBTQ students and others experiencing mental health issues and provided vital community resources and support groups to the larger campus population. But given the office was one of the first of its kind, Toy and others faced many challenges. Most problematically, it had no immediate model to emulate. Therefore, the LGBPO looked to organizations sponsoring students of marginalized identities other than their sexuality, such as groups for people of color, and worked to maintain close relationships with them. However, Toy found that students identifying with a minority group and as queer felt uncomfortable in spaces which only addressed one aspect of their marginalized identity (Task Force, Jim Toy Papers, Box 7). Numerous students identifying as a particular ethnic background AND queer were often referred to the LGMPO (Lesbian Gay Male Program Office), renamed from the Human Sexuality Office. This was because these organizations viewed the challenges faced by QPOC (Queer People of Color) as those faced purely by LGMPO. There was no consideration of the issues related to the intersection of race/ethnicity AND the subject of “queerness.”

Toy understood the intersecting oppressions that many people on campus and in the community faced and emphasized the interrelated dynamic of seemingly different issues. He also knew the depths of the system that needed to be changed in order for LGBTQ youth to feel safe in their surroundings and have full access to their rights. There is no question that his own lifetime experiences must have underscored how he came to understand the important and complex challenges that faced the Spectrum Center.

Toy’s involvement in multiple organizations across the community, insistence for an accessible spaces for the organization’s office and consistently holding the University administration accountable for their perceived homophobia reflects his insistence, energy, and experiences that have charged his commitment to social justice in complex ways. This was influenced by his His efforts to create an equitable community space for LGBTQ students reveal his understanding that eliminating one type of oppression only leads to considering multiple forms of oppression in a society that marginalizes an assortment of identities which are sometimes distinguishable but more often intersecting.

In narrating his activist life, however, Toy, who is Asian American, rarely mentions direct participation in AAPI causes. When asked how Asian American and LGBTQ issues intersected, Toy replied:

“Asian American and TBLGQI issues intersect in all our struggles for justice and equality, our attempts to gain and retain our human and civil rights. We must work for our civil rights at federal, state, and local levels. Gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation are absent from federal non-discrimination policy and State of Michigan non-discrimination policy. Similarly, gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation must be included in State of Michigan "hate-crimes" policy.”

Toy serves as an inspiration for many in the Ann Arbor LGBTQ community, especially those who identify as both Asian American and queer. He is a powerful symbol for A/PIA activism as a visible Chinese person taking on roles to advocate for all queer people, influenced by his own experiences at the intersections of race and sexual identity. Today, he continues his fight for equal rights for all in Michigan and around the U.S. In particular, he has been a fierce ally for the transgender community in light of bathroom bills and attacks on trans-healthcare. When asked about his message to Asian American youth struggling with their sexuality and their place in civil rights activism, Joy replied,

I don't give advice--I try to help people look at the pros and cons of taking any action that they may be considering. That said, my "identity" is a tapestry of many threads--race and ethnicity, color, class, gender identity, sexual orientation, ability/disability, appearance, age, religious belief, political belief, etc. If one of the threads is plucked, the whole fabric is bound to move. Anyone struggling to consolidate and manifest any thread of their identity may find help from allies--and possibly from counseling or therapy.Jim Toy. Interview With NBC News.

References

https://alumni.denison.edu/citations/james-w-toy/

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/billi-gordon-phd/jim-toy-advocate-extraord_b_9343334.html

https://spectrumcenter.umich.edu/node/58/

Gay Advocates Office Questionnaire. Student Responses. Folder 1. Box 7. Jim Toy Papers. 1992-1993. Bentley Historical Library. University of Michigan.

LGMPO Reorganization. Office Direction, Jim Toy to Maureen Hartford. Emails and Attachments. Folder 2. Box 7. Jim Toy Papers. 1992-1999. Bentley Historical Library. University of Michigan.